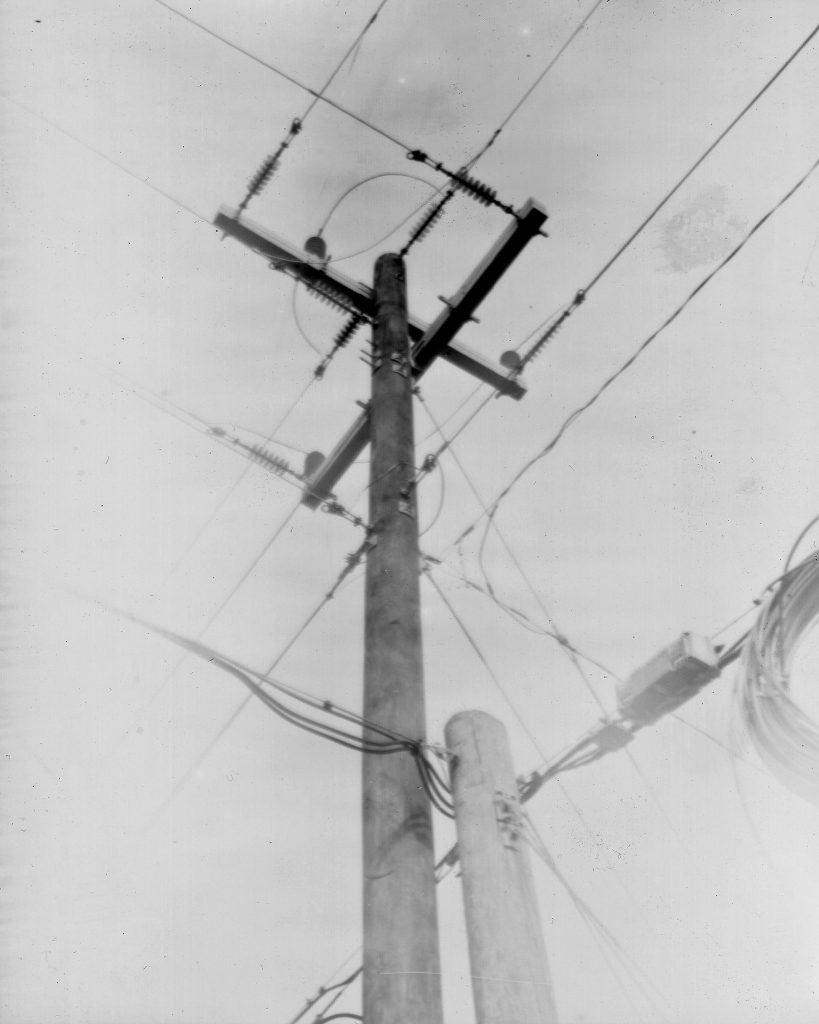

I recently bought a cool old-timey (from 1896) folding “pocket” camera at a local garage sale and here is my first photograph! It’s so stinkin cool! (click for full size)

If you care to know more, here are all the gory details!

The Camera

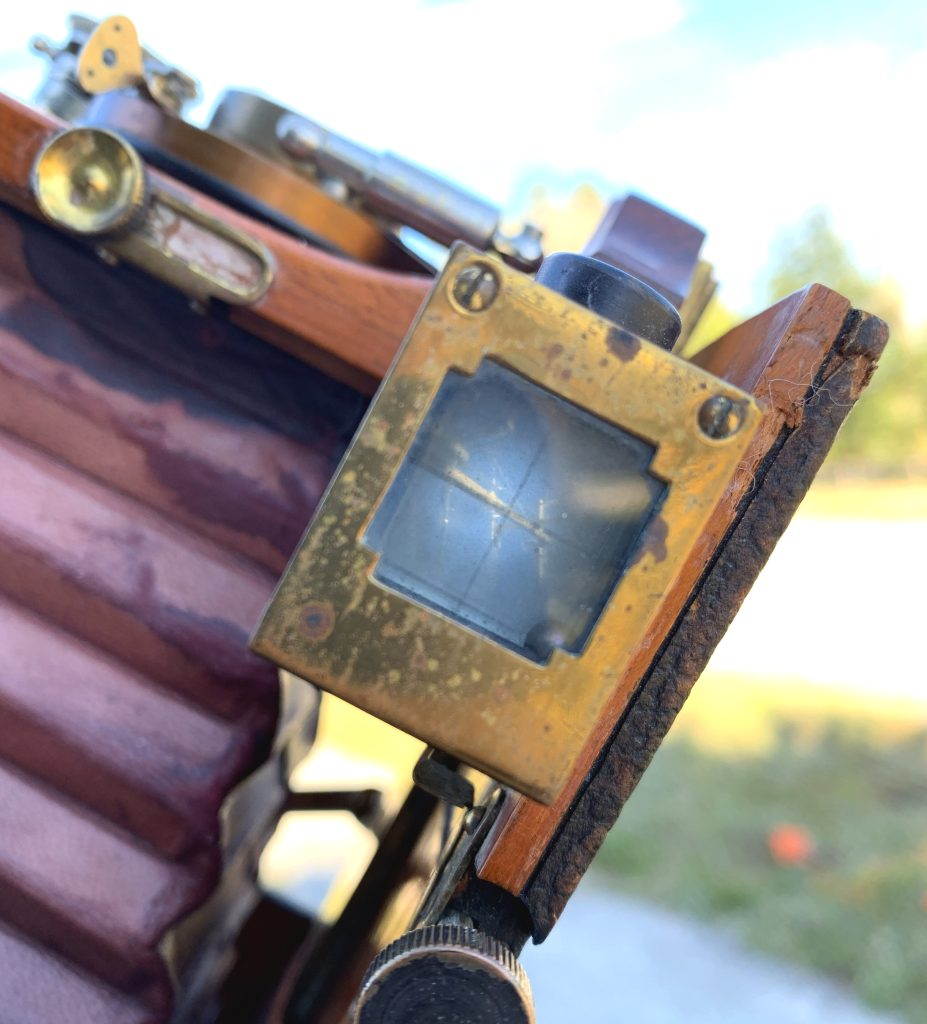

The camera is a folding Rochester Cycle Poco No. 2 model from 1896.

It’s a beautiful little portable foldable camera. It’s mostly made out of wood except for the actual iris/lens/trigger part. It folds up into a pretty small box that measures 6 inches by 6 inches by 3 inches.

The trigger mechanism was locked up when I bought it, but it took it completely apart and cleaned everything and put it back together and it works fine now. Well, except for the timer part. The timer mechanism is really cool. It’s not a mechanical timer. It’s a pneumatic timer, meaning it pushes air through a tiny hole in a pneumatic cylinder for slow controlled repeatable movement. In the below photo, the pneumatic cylinders are to the right and left of the central lens.

Sadly, the pneumatic cylinders are completely locked up and I could not break them free without busting them, so I just disconnected them and I’m using the camera in manual, or bulb, trigger mode.

This is fine, though, since the “film” available for this camera is only ISO 2, which is a very very slow film. Meaning the shutter has to be left open for a while in order for the slow film to gather enough light. Even in full sunlight, the shutter needs to stay open for a quarter or even a half a second, which I’m pretty capable of operating manually.

The “Film”

This camera doesn’t actually take film though. It exposes light to a 4 inch by 5 inch glass plate, known as a dryplate , that’s been coated with a thin layer of light sensitive silver gelatin . Flexible plastic photographic film was invented in the late 1880s, but was not super popular when this camera was sold. Most cameras of this era used glass dryplates.

I bought some hand-crafted hand-coated glass dryplates from a small online company in Slovenia. The company is called Zebra Dry Plates , so go check them out! They also have some really great alternative photography videos on their YouTube channel !

The camera comes with several cool wooden holders for exposing light to the plates. The holders are reversable so each holder can actually carry and expose 2 separate plates. You have to load your glass dryplates into these holders in a completely dark room or a room with only infrared light in order to keep from exposing your “film”.

First Photo Scene

I decided to take my first photo of a power pole near my house. I thought this scene would give me some good contrast between the wooden pole and the bright sky. Plus nothing would be moving in this scene. Other than my camera a bit maybe during my long exposure triggering. Also, this is a very repeatable scene if I really screwed it up and had to do it over again later.

This camera has a cool little optical view finder with a tiny ball bearing inside that doubles as a level. It’s that little copper colored box in the upper right of this image:

This view finder uses a mirror or prism to optically project the scene, although upside-down, so you can frame it up properly. You don’t actually put your eyeball up to it like modern viewfinders. The image is projected pretty clearly onto a glass plate. I really don’t fully understand it. It’s amazing though.

Focus

I used the tissue paper method to focus the image inside the camera.

If you place a piece of thin tissue paper into the same plane that holds the glass dryplate, you will be able to clearly see the image being projected by the camera lens onto the other side of the tissue paper. It’s like a little movie projector on the back of the camera!

Yes, it projects upside down. That’s actually how lenses work.

You really have to block out all sunlight to clearly see the focused image on the tissue paper. And that totally explains why old-timey photographers would duck under a black velvet curtain to look into the back of their cameras!

Exposure

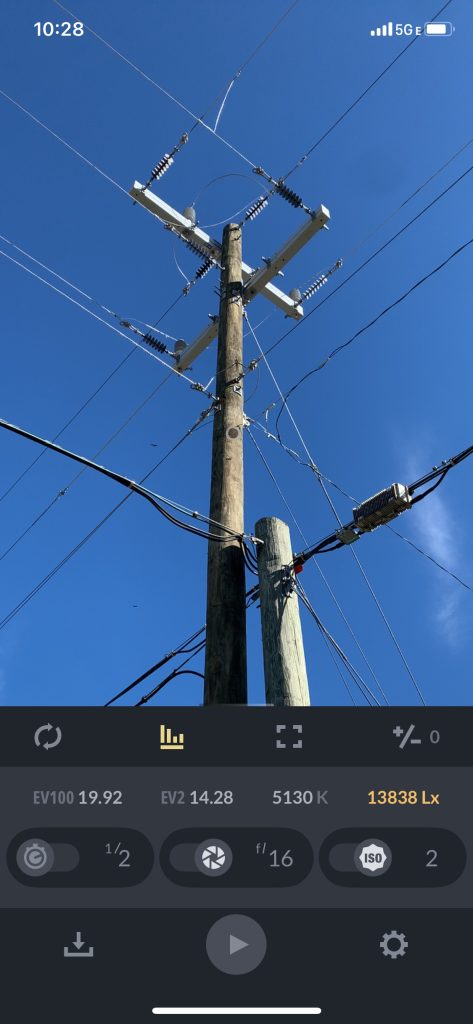

I used a free light meter app on my phone to tell me how long to expose the glass dryplate based on the current lighting in the scene, the ISO rating of the glass dryplate, and the f-stop, or iris opening, of the camera lens.

You basically just show the light meter app the amount of light in your scene by using your phone’s camera. And then you set the ISO value of your film. Then you can either set the exposure time or the f-stop iris value and the app will calculate the remaining variable.

In this scene my film was ISO 2 and so I adjusted my f-stop to 16 in order to get a half-second of exposure time which I could just manually count off in my head. It did not have to be perfect. The film emulsion layer on the glass is slow so if I gave it a little extra light, it won’t actually overexpose it and ruin it. I could also compensate for some over or under-exposure during the development process. Which I performed myself.

In my case I also varied the lighting in the scene a little bit by waiting for the sun to come out from behind the clouds. I wanted this first test photo to have high contrast, so I did not want to take this photo under cloudy lighting conditions.

Developing

This was my first time developing photos, so I was pretty nervous about it. But it turned out to be not terribly difficult. I bought the trays and the developer chemicals and the fixer chemicals online at B&H Photo . I watched a few of the instructional videos from the Zebra Dry Plates company . And it tried it and it worked pretty well.

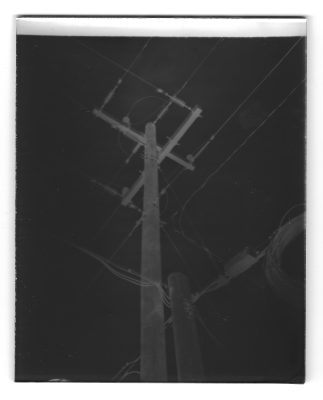

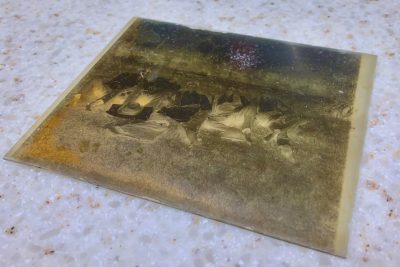

Once developed, fixed, and dried overnight, the glass dryplate showed a pretty nice negative image of the scene, like so:

Scanning

I then scanned it in my flatbed scanner at high resolution like so:

Correcting

And then I used my favorite free Photoshop clone, Paint dot net , to invert the negative into a positive and then to stretch the levels to give it dark blacks and light whites, like so:

I’m really quite pleased with my first old-timey photo. The small dust-like imperfections in the emulsion are real and are very similar to real photographs from that era. The fading or vignetting towards the edges is either due to the old-timey lenses in the camera, or is possibly due to the non-perfect hand-crafted light sensitive layer on the photographic glass plate that was used to capture the light. And that’s also actually not that uncommon for that era.

My first photo is a little bit blurry, which is also not uncommon for this old-timey technology. There’s some chance that my focus was a bit off. But there’s even more chance that the camera shook a bit during my manual triggering of the half a second exposure. For future photos, I will see if I can find a remote trigger to remove the possibility that I’m shaking the camera during triggering. And I also have an idea about how to fine tune and perfect the focusing of this camera.

Thanks!

So what do you think I should take an old-timey photo of next? Let me know in the comments!

Thanks for your interest!

Kurt